In the late 12th century, a young Leonardo Bonacci — better known as Fibonacci — traveled with his merchant father from their home in Italy to Algeria (North Africa). They landed in the gorgeous port city of Bugia, now known as Bejaïa, where Fibonacci set about learning mathematical ideas from the local vendors. It was in the marketplace that he observed the use of Hindu-Arabic numerals, 0-9. They were so much more efficient than the Roman numerals that dominated Europe.

In 1202, Fibonacci published Liber Abaci. Use of Hindu-Arabic numerals spread through Europe like wildfire.

____

My telling of this story is Eurocentric. It centers on a white man who is credited with popularizing our current numeral system in Europe. It’s important to note that this man neither invented nor offered his own variation on these numerals. This is not to say he wasn’t a brilliant mathematician in his own right — I love Fibonacci’s work! — just that these numerals were already in use all over the world. They have origins in India in the 6th or 7th century, and I doubt that the Indian mathematicians would have viewed this story as worthy of note in their mathematical history books. Fibonacci then learned about them from Algerian merchants. (The fact that I felt the need to specify that Algeria is in North Africa alone is so Western. Americans do not know where Algeria is, despite the fact that it’s the largest country in Africa by land mass, and the 10th largest country in the world.)

If my research tonight is correct, we should thank Muslim scholars al-Khwarizmi and Al-Kindi for introducing the ‘Christian world’ to these numerals years before Fibonacci’s Liber Abaci was published.

I wish I had done that research before today — before I went and taught a third class about Fibonacci. Our goal with this lesson was to disrupt the third grader’s ideas of who does math. We wanted to showcase the importance of mathematicians in non-Western, non-white parts of the world. (Thank you, 12th century Algerian merchants! We could still be using Abacuses right now!) Even though the articulation of the lesson has its faults, I am proud that the classroom teacher and I were able to swiftly take action and start this work.

____

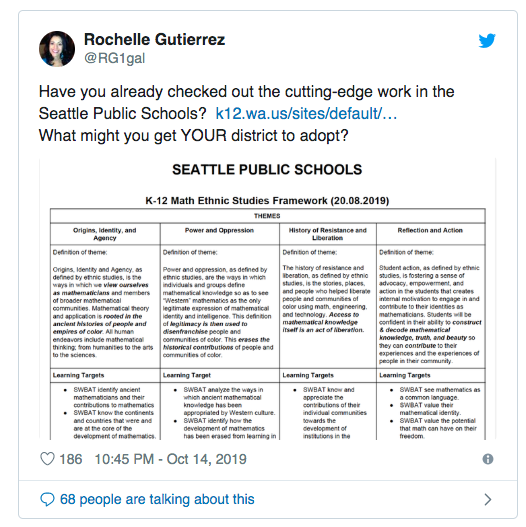

With a recent tweet, Rochelle Gutierrez (@RG1gal) drew my attention to Seattle Public Schools’ math ethnic studies framework. This framework was created by Tracy Castro-Gill (@TCastroGill), Norman V Alston (@fearnonumber), and Shraddha Shirude (@ESMathTeacher).

Have you already checked out the cutting-edge work in the Seattle Public Schools? https://t.co/VIZNCMshQ1

What might you get YOUR district to adopt? pic.twitter.com/gdQwlIL3W6— Rochelle Gutierrez (@RG1gal) October 14, 2019

I skimmed over the document, knowing that it would take many, many reads to digest. It’s not often a SWBAT statement takes my breath away. “SWBAT analyze the ways ancient mathematical knowledge has been appropriated by Western culture.”

Like a punch to the gut.

That’s when I started thinking about Fibonacci.

This morning, I visited a third grade class that was hard at work representing numbers. The teacher had introduced them to expanded form. “1,029 is like 1000 + 20 + 9,” Louisa told me. “It’s helpful to see all the place values.”

I smiled and nodded.

Imagine trying to write those giant numbers in Roman Numerals. The sleek and elegant 48 is XLVIII, and 49 is XLIX, and then comes L: 50. So 48 uses 6 characters, while 50 only uses 1. Surely computation would have been cumbersome, which explains the prevalent use of the abacus.

The Hindu-Arabic numeral system revolutionized math in Europe. I wanted to share with students who significant this was, and also that this innovation came from Africa. Their knowledge of Africa is very limited. (Some seem to know of it only within the context of slavery, and while I’m glad that people have started conversations about slavery with them, it’s criminal that this is the only frame of reference for an entire rich and diverse continent!)

“Can I come in later today during read aloud?” I asked the classroom teacher. “I have a book I want to share, about Fibonacci.” I explained how I’d seen the math ethnic studies framework, and how I wanted to help show how people in Europe appropriated mathematical understandings from people in Africa and Asia.

The classroom teacher was enthusiastically on board! “We only have 15-20 minutes,” she told me, “but let’s do it.”

______

“Today, we are going to read a story about a mathematician named Fibonacci,” I told the third graders. “He’s from a city in Italy called Pisa.”

“And he traveled to a city called Bugia, now known as Bejaïa, where he learned a lot about math.”

“Let’s learn more about what he learned from the brilliant mathematicians in North Africa. Here’s Blockhead: The Life of Fibonacci, by Joseph D’Agnese, illustrated by John O’Brien.”

The children were fascinated by the story of Fibonacci struggling to fit in at school as a child.

“Is that really what his teacher said to him?” Charlotte asked, incredulously.

“Well, no, this is the author’s imagining of the story. The details are from the author’s mind, because he wasn’t there. And Fibonacci’s teacher spoke Italian.”

“I know about the Fibonacci sequence!” piped up Josiah from the back of the rug. He would announce this at least 6 other times as we read the book.

I paused a lot more for emphasis during the part about Fibonacci traveling to Bejaïa. We discussed what it means to be a merchant, and how much Fibonacci, an incredible mathematician, learned from other people. This felt like as good a time as any to emphasize the benefits of collaboration and exchange of ideas. Of course, it’s not clear to me that Fibonacci exchanged any ideas with the merchants in Algeria. Maybe he just observed them, and learned from them. I wonder if he contributed anything at all to them, or if his mathematical contributions to the world didn’t come until later.

I wanted to share with them my connection to Algeria — not to be self-aggrandizing, but because I wanted them to see that this is a real place, with real people, who really changed how people — specifically white people — worked with numbers.

During my lunch break, I had pulled up some photos that I took on a visit to Bejaïa. My husband is from Algeria, and we try to make regular visits back to visit my in-laws. My husband’s family is from another part of the country, but he actually attended middle school in Bejaïa. It’s a gorgeous port city — epic swimming enclaves, and mountains running straight down into the sea. The city itself is much older than the European settlements in the US, and the buildings are a conglomerate of Arab, African, Mediterranean, and French influence. “While that boat isn’t like one that Fibonacci would have seen,” I told the third graders, “the fact that this is a city on the water is important. It brought in people from all over the Mediterranean, and they exchanged both goods and ideas. That’s what mathematicians do — they collaborate.”

I showed them a photo of my husband and daughter, then only 1 years old, enjoying a walk along Cap Carbon, just outside the downtown area.

“He’s from Africa? But he’s white!”

I nodded. “He has very light skin, yes. People from Algeria have all different skin colors. His happens to be on the lighter side.” I didn’t want students to think that these Algerian merchants were more worthy of sharing ideas because they may have had lighter skin than their sub-Saharan counterparts. There have been important mathematicians, to which we owe a great deal of gratitude, all over the continent. The fact that Algerians are lighter than the Nubians has nothing to do with his worth.

We also talked about how this system is not the Arabic numeral system, but one that was first identified by Indian mathematicians hundreds of years earlier.

“Do you mean Indians like the people that used to live here? Or like… the people that live in India?” Sammy asked.

“I mean the people that live in India, on the Indian subcontinent,” I clarified. “The indigenous people of North America also had important mathematical ideas. But we don’t have good records of all of them…” I trailed off. Because we systematically killed them and erased their culture? That’s not exactly a flip comment to make to a room of 8 year olds. There are also issues with lumping in all of the indigenous people of North America together all the time. It’s like an entire continent, composed of separate and sovereign nations. Should I talk about that?

I looked at the clock. We were 18 minutes in to our 20 minute block. I took out my computer to show the third graders one minute of a video I found on YouTube showing an Algerian marketplace, and a fictional Fibonacci walking through. “These are the brilliant mathematicians we are taking about,” I said. Mathematicians aren’t just white men in tweed sweaters.

There. Twenty minutes had come and gone. I checked in with the teacher, who thought this was a good start. We disrupted some of the students’ internal narratives around who mathematicians are, and where they come from. The boy that had talked to the most and most emphatically throughout the interactive read aloud happened to be Josiah, the only black boy in this class.

But I also felt like I had fumbled at parts. There were important ideas that were omitted, responses to questions that I tripped over, and, more importantly, still a focus on the white guy. Planning for this work must be done deliberately. There’s only so much I can do when I’m working on the fly. I’m still early in my journey towards culturally proficient teaching and anti-racist practices.

This work is challenging. The framework is bold and needed, and now comes the hard work of bringing it to life in the classroom. How do we make this a reality?

“Come back any time to do another read aloud!” the classroom teacher told me. She mentioned the experience to her grade level colleagues, too, at a team meeting later that afternoon. “This is important work!”

I think I will. Which book is up next?

Lovely work Jenna! Great that you’re able to bring your personal experience to this!

I’ve probably already shared my own work with Grade 3 around this, but here it is again, just in case:

http://followinglearning.blogspot.com/search/label/Fibonacci

There are so many directions this can go in; becoming more aware of non-European cultures is definitely a major part of it. We need a picture book about al-Khwarizmi!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much, Simon! I always love to read your blog. I don’t remember either of those posts — and even if I did, there is always more to dig into. Some of the visuals are quite arresting. I’m fascinated by the image of using Cuisenaire rods to model base 6, from the Jan 2016 post, and the color coded roman numerals from 2015.

Do you want to write the al-Khwarizmi picture book? 🙂 I’ll give you a good quote for the dust jacket.

LikeLike

Do you intentionally use a globe to counteract the distortions of most school maps that show Europe to be much larger (important?) than it actually is?

LikeLike

Fascinating! I hadn’t thought of that, but it’s an excellent reason to use a globe. I wish I’d been that deliberate. (Originally, I had envisioned fancy graphics on a slide deck, but reality set in and… dry erase markers won out.)

LikeLike

Thank you!

This is both accessible and do-able.

Will be sharing in my district.

BTW: Didn’t know about the Seattle project. Will be exploring that.

Jacob

LikeLike

Thanks, Jacob!

I learned about the Seattle re-humanizing mathematics project only last week. It’s fascinating, but I’ll need to read the framework at least 200 more times before I feel like it’s settled in. There’s a lot there, and I’m not sure what all of the ideas might look like enacted in the classroom.

LikeLike