“Sit down, Daysha… Daysha.”

Six-year-old Daysha shot me an icy glare while she leisurely pumped hand sanitizer onto her open palm. The rest of her class was all sitting on the rug, engaging in our problem string. I sighed, trying to remain patient but persistent. I reframed my request.

“Come join us, Daysha.”

Truthfully, I don’t know her very well. I have only taught in her classroom for a few days now, all while her classroom teacher was out sick. Many of her classmates seem to be falling over themselves to share their mathematical thinking with their peers. Daysha seems to be more concerned with finding distraction. She walks around the room. She washes her hands. She blows her nose. She helps clean up a the spill from another student’s water bottle. When she does sit at the rug, she faces away from the central part of the lesson. She plays with a friend’s hair.

I recoil at my attempts to control Daysha, but, in the moment, I wasn’t sure what else to do. I know that Daysha’s classroom teacher is concerned about her progress in math class, and Daysha’s laps around the room feel defiant. What is she avoiding? How will she make progress if she does not engage? Why won’t she engage?

Still, I’m acutely aware that compliance is not engagement, and that there’s a deep history of oppression around trying to control the bodies of black children. Daysha might only be 6 years old, but she knows there’s something desperate about my pleas.

I don’t know Daysha well enough to know how she feels in the classroom. How do others welcome her? Does she feel like her ideas are valued? I know the classroom teacher cares deeply about Daysha. The classroom teacher has worked hard to cultivate an inclusive and trusting environment, but the world doesn’t exist in this bubble. Everyone in the classroom — including Daysha — is bringing in the legacy of their outside experiences, too. We’re trying to build a group identity as well as strong individual identities, and this identity work can be exhausting.

So instead I decided to invite Daysha up to the board.

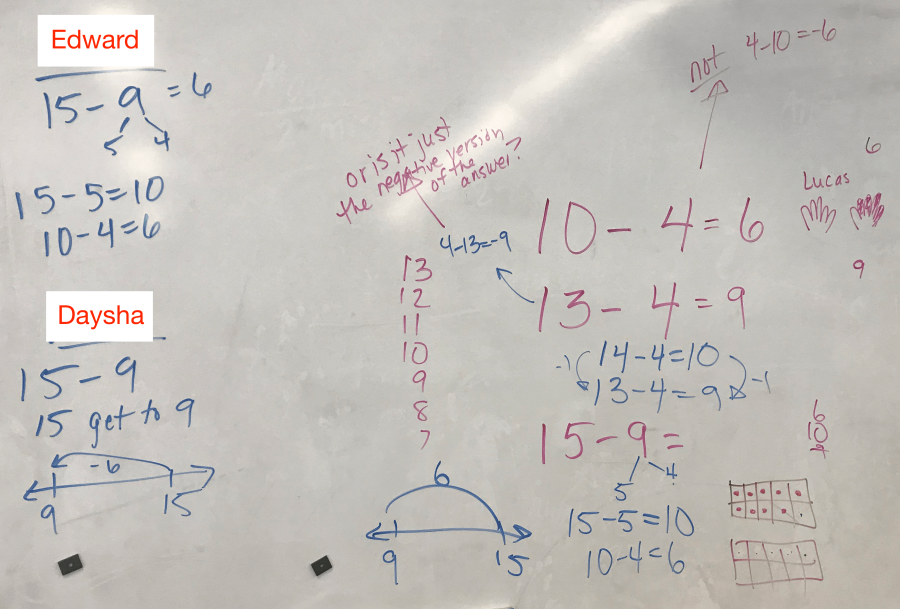

We were working on 15 – 9. Edward had already shared his thinking: “I break up the 9 into 5 and 4, because I know 15-5=10. Then minus the 4 and it’s 6.” I had annotated his thinking on the board.

“Hmm… I wonder how we can show 15 – 9 with a picture,” I mused aloud.

“How about a ten frame?” Gilad suggested. I drew out twin ten frames, and marked 15 dots.

“Hey, Daysha, can you help check if this is right? Are there 15 dots?”

Daysha blinked. She looked surprised. “Huh?”

I pushed again. “Are there 15 dots here?” A pause. “You can always come up to the board if you want to check.”

Then — to my own surprise! — Daysha started to walk towards the board. She counted each dot, blissfully unaware that Jeremy in the back had whispered “you don’t need to count! You know there’s 10 [in the ten frame]!” Daysha was in the zone.

I urged her to consider how to represent 15 – 9 using the ten frames. Daysha bit her lip, unsure of how to proceed, and I worried that I had pushed her into too vulnerable a place in front of her classmates. So public!

“So… do I try to get to 9?” Daysha erased the last 6 dots, counting each one. “1… 2… 3… 4… 5… 6.”

Edward had thought of 15 – 9 as a separating or ‘take away’ situation, in which he removed the 9 from the 15. Daysha had brought some new and fascinating thinking to the table! She was comparing 15 and 9, and determining the distance between them. She hadn’t just erased the dots to make 9, but she had kept track!

Edward had thought of 15 – 9 as a separating or ‘take away’ situation, in which he removed the 9 from the 15. Daysha had brought some new and fascinating thinking to the table! She was comparing 15 and 9, and determining the distance between them. She hadn’t just erased the dots to make 9, but she had kept track!

“Daysha! What an amazing question!” I gushed. “You’re looking at the problem in a different and really exciting way. Let’s see if it works.”

We tried it out, and then compared Daysha’s answer of 6 to Edward’s.

Kylie, Daysha’s best friend, lit up. “Daysha! The answers are the same!”

In the top left corner of the board, I recorded these two strategies, naming them after the student that shared them. “Edward’s Strategy,” about making 10s, and “Daysha’s Strategy,” about determining the distance between the two.

I worry that some of our responses to Daysha’s success were so effusive that she might think we were surprised that she had something brilliant to contribute. Truthfully, I was more surprised that she was willing to participate, something she hadn’t done the previous day at all. But even that is a low expectation. The comparison to Edward’s strategy is something standard that I do — we compare and contrast! — but I don’t want to communicate the message that we have to measure the black girl’s success against the white boy’s. That’s dangerous.

My relationship with Daysha is still so new. I want to understand how she feels about math class so that I can make changes that will improve the experience not just for her but for many other students. Islah Tauheed wrote a beautiful post for Heinemann about radical empathy, and how engaging in radical acts of empathy transformed the entire classroom experience — for her and her students. It’s what I aspire to.

There were some definite successes during this lesson, and I continue to question where I can improve.

I had Daysha stay up at the board with me to model how to play a game. (Subtraction 5-in-a-row, from Marilyn Burns/@mburnsmath) Daysha seemed to be much happier in the spotlight, even with some unsteady thinking as she worked through some subtraction problems. I found her completely willing to share her incomplete and unpolished thinking when she was positioned in front, and totally unwilling to think when asked to sit with her classmates. What about her physical position within the classroom makes such a difference? How can we recapture this magic in different places around the room?

For the rest of the class, students referred to Edward’s and Daysha’s strategies. We reinforced their competence.

_______

Assigning Competence

This reminded me of the quote from Deborah Ball’s session about discretionary spaces and race and discourse at the Teacher Development Group’s Leadership Seminar and NCTM 2019.

c/o Kevin Dykema (@kdykema)

c/o Kevin Dykema (@kdykema)

Even without knowing the context in which this quote was given, it holds power for me. I think that discourse and discussion are still structures that are likely to benefit student learning. With that potential for reward comes a potential for risk — “a risk of reproducing patterns of racism and marginalization.” It’s not to be taken lightly.

In reviewing these techniques and strategies for assigning competence, as outlined by University of Michigan Professor Deborah Ball, I realized that I used a few of them with Daysha. I publicly named her competent move. I wasn’t overselling her idea, either. It deepened our class’ conversation and pushed our understandings in a new and exciting direction. Daysha’s contribution was invaluable. I recorded it publicly… with her name. Students continued to use “Daysha’s strategy.”

And even with these powerful moves that I think contributed to Daysha feeling more welcome, I worry about the moves I made that may have inadvertently harmed her. Maybe she feels more competent now, and maybe she’ll remember me trying to get her to sit down. I don’t know. I think my heart was in the right place the entire time, but I am a product of my own environment, and it’s ultimately about the impact on the students. I’m excited to see Daysha again so that we can continue to develop together.

I’m excited to hear more of her ideas around subtraction, too. I think her mathematical ideas are more powerful than she knows — and I want her to know how powerful her mind is.

Thanks for this reflective, real shop talk.

LikeLike